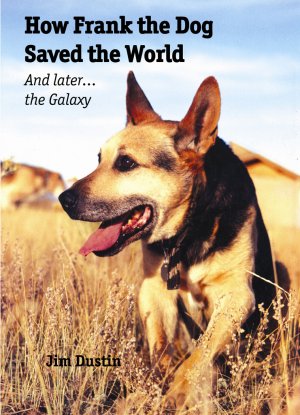

How Frank the Dog

Saved the World

And Later...the Galaxy

by Jim Dustin

Chapter III

Democracy has come to the

world and flourishes in Greece in the 5th Century, B.C. The city-state of Athens

rules the Aegean

and influences the politics and behavior of half the Mediterranean basin. It

gives birth to the voices of Aeschylus and Sophocles, Aristophanes and Plato.

But while it practiced democracy at home, it kept 1,000 cities under its

imperial thumb. Many rebelled. One was Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Athens

sent an army to besiege the city. After it was taken, the noble Athenians

executed 1,000 men for the crime of wanting to be free to govern themselves. In

416 B.C., Athens tried to force neutral Melos into the war against the

Peloponnesian League. When Melos refused, the noble, freedom-loving Athenians

killed all the men and sold the women and children of Melos into slavery.

Humankind hardly needed to

provide more evidence for the prosecution, but there they were, further

incriminating themselves even as the Judgment Ship approached. But then, they

didn’t know about the Judgment Ship. Many of them were living their petty little

lives as if there was no quid pro quo in life.

Dogs are flexible. They not only

can twist and jump and squirm like no human, they also have more chromosomes

than humans. Plus, they have short life spans. They can breed at about one year

old, and breed again and again. Thus, it is fairly easy to produce specialty

breeds of dogs. And from that one original dog ancestor, hundreds of breeds have

emerged.

About

all these breeds had in common was that they were bred to serve some purpose

decided on by humans. Dogs were bred to hunt, they were bred to kill vermin,

they were bred to guard, they were bred to locate what humans wanted, they were

bred to haul, they were bred to carry, they were bred to look pretty, they were

bred to be mean, they were bred to be big, they were bred to be small, they were

bred to retrieve, they were bred to search, they were bred to point, they were

bred to run, they were bred to herd, they were bred to watch. And some were bred

to fight.

Frank

was the product of a breeding experiment to cross a pit bull terrier with a

German shepherd. The idea was to produce a fighting dog with the tenacity of a

pit bull and the strength and weight of a shepherd. The product of the effort

was a squat, muscular dog with a big head and powerful jaws. To look at him from

afar, you’d have to assume the chunky mutt was a fighter, a

look-over-your-shoulder dog; one that made you walk a wide path around him, then

look over your shoulder to make sure he wasn’t following. Frank had that kind of

Ty Cobb aura - the competitor who was a damn good ballplayer but just a little

bit too tightly wound for his teammates’ comfort.

If you

could get by that stiff-legged, head-high posture, if you could get close and

kneel down in front of him, look into those expressive dark eyes, you’d see a

personality yearning for just a smidgeon of kindness. Because you’d also see

that scarred left eye, and you’d also notice that slight limp and the scars on

his nose and legs. You’d realize he’d been hurt repeatedly. You’d notice that,

but you wouldn’t have been Billy Bob or Lenny Callaway.

Frank

wasn’t named Frank originally. He was named, with a singular lack of

imagination, Killer. He had seemed to grow into the name because, as he filled

out, he looked formidable. He had the brown fur and black saddle of a shepherd

and some of a shepherd’s bulk, but he also possessed the low-slung, bowlegged

carriage of a pit bull. He also had that species’ squarish head and powerful

jaws.

Billy

Bob and Lenny took good care of Killer when the dog was young. Killer got a lot

of raw meat on the theory (a word with which the Callaways were not familiar)

that raw meat encouraged aggressive behavior. The dog got a lot of walks and

play - if you could call what Billy Bob and Lenny did play. Killer loved most of

it. He loved grabbing on to a stick and holding on to it no matter what the men

did. They could actually lift the dog off the ground and swing him around

without Killer losing his grip. They’d time how long they could swing him in

that manner. Always, their arms gave out before the dog’s jaw muscles did.

Killer

also loved to run, although that wasn’t his forte. Killer kind of looked like a

speeding tank when he ran, all leg movement and no body movement. Plus, he

tended to run through things rather than around. The mixed-breed puppy looked

kind of weird when in motion, but the Callaways didn’t care; the dog was growing

up strong.

However, he wasn’t growing up mean. Killer had the natural instinct of pit bulls

to be antagonistic to other dogs. Killer failed to follow through, though. He’d

run up to other dogs in a belligerent manner. The stranger dogs would usually

give up on the spot, lie down and extend their necks. That was sufficient for

Killer, who probably should have been named Intimidator, but that was another

word the Callaways didn’t know. Establishing dominance was enough for Killer.

He’d trot over to Lenny or Billy Bob expecting some sort of reward for defending

the turf against another dog only to be yelled at or kicked.

“Kill

the damn dog, you stupid,” one or the other would yell, and drag Killer over to

the other animal unaware that as far as dogs were concerned, the issue was

settled. Those were the first times Killer was hurt, when he was dragged by his

spiked collar. He tried to keep up, but those stubby legs were no match for the

long strides of the men. He became afraid when either of the two men would

approach, their anger apparent, and reach down to grab that collar. It hurt, and

Killer couldn’t fathom why was being hurt. In his world, the dog protected the

turf and his masters. He had defeated intruder after intruder. What was he doing

wrong?

“You’re not making him fight for his food. If the dog ain’t born mean, you’ve

got to stick mean in ‘im,” Dad Callaway intoned. “It’s like Lenny there. He was

God’s own coward afore we started taken ‘im to the roadhouses. Ain’t that right,

Billy Bob?”

Billy

Bob smiled a gap-toothed smile. He remembered. Billy Bob liked to fight. He was

the best bar fighter in the county. He stood 6-foot-5 and weighed 260 pounds.

And strong. He could bale hay from dawn to dusk, hoisting 100-pound bales one

after another into the flatbed truck as high as the man on top could stack them.

He could handle a chain saw with one hand, split wood in the evening after

dinner and earn a living as a hod carrier when he wasn’t working on the hard

scrabble this family called a farm. Dad Callaway had taken to hauling Billy Bob

out of the county to fight because no one within 50 miles would take him on any

more.

Lenny

was ten years younger than Billy Bob, and only a half-brother. Dad Callaway

liked to remind Lenny that Lenny didn’t have Billy Bob’s genes. That’s because

Dad Callaway’s first wife and her genes had disappeared after one too many of

Dad Callaway’s beatings. The same thing happened to Lenny’s mother, and after

that, purt near every woman in that county and all the surrounding ones didn’t

have anything to do with the Callaways.

So

Lenny hadn’t grown up with Billy Bob’s bulk, nor did he have Billy Bob’s cruel

streak, or at least he wasn’t born with it. Billy Bob liked to kick a man in the

ribs a few times even after the man had been knocked unconscious. Or Billy Bob

liked to slam his heavy work boot down on a man’s hand as he was lying helpless

on the floor. He said he wanted to know if the man still had feelings after

being knocked cold. Then he’d laugh until spittle ran out of the side of his

mouth.

Lenny

ran with some other kids when he was younger, though he hadn’t gone to school.

The Callaway “farm” was situated way back in the woods off a dirt road that ran

from a gravel road that connected to a two-lane paved county road that led

eventually to a two-lane state highway. School officials didn’t even know Dad

Callaway had had a second son. Their home was a couple of old trailer homes

surrounded by old cars and furniture. A gully that ran by the dwellings served

as a landfill, clogged with tires, useless appliances, bottles and other trash.

Lenny

ran with a bunch of kids from similar circumstances, so he was familiar with

certain bars by the time he was 17. Those bars were rough places, and Lenny had

been beaten up more than once. “We gotta toughen your ass up, boy,” Dad Callaway

announced one day. For the next year or so, whenever Dad Callaway felt like

Lenny needed some training in the manly arts, the three of them would hop in the

old Dodge pickup and head down Interstate 55 to find some roadhouse. The bar

might be in southeastern Missouri, or northeast Arkansas, or Tennessee, or

sometimes even as far away as Oklahoma. They had to get away from where Billy

Bob was known, and none of them worked steady anyway. It wasn’t like they were

losing a paycheck.

When

they’d find a bar, they’d send Lenny in. Lenny’d have a few beers while his

half-brother and father would sit outside, boozing in the pickup. Then they’d

wander in a little later and sit at a table away from the bar. That would be

Lenny’s signal to start a fight with someone at the bar, and that someone had to

be fairly big or Dad Callaway would beat up Lenny himself for picking an easy

target.

If

Lenny won the ensuing fight, fine. If he was losing, Billy Bob would step in and

beat the crap out of the other fellow. Billy Bob showed no mercy in those

instances. Billy Bob used to have some friends; Billy Bob was 39. All his

friends were either dead, in jail, or just gone. All he had left was family. All

he had left was blood, and as far as Billy Bob was concerned, anyone who was

fighting Lenny was trying to kill Lenny. Anyone who landed a punch on Lenny was

going to have Billy Bob trying to break his ribs and ram the broken bone into a

lung. And if things got too out of hand, Dad Callaway was sitting there with a

knife in his boot and a .380 and a .38 in either pocket.

It was

Killer’s misfortune to be delivered into this family. Not mean enough? Dad

Callaway had a treatment for that. If the father was willing to subject his own

son to such treatment, he had no hesitancy whatsoever in visiting such cruelty

onto a dog. It was the Lenny treatment, only worse, because Dad Callaway didn’t

really care if the dog lived or died. There were lots of dogs. Killer only had

two things going for him: The Callaways thought he might be worth something, and

the entire family didn’t have the IQ equal to that of a pin oak. Had they been

able to find dogs vicious enough to put in a cage with Killer, Killer probably

wouldn’t have survived. Finding such dogs wasn’t an easy task, and finding such

dogs without having to spend some money was an almost impossible task.

In

their crooked neck of the woods, those that had vicious dogs fought them. The

winners got kept, the losers got killed. It was a sport in certain regions of

America where people gathered in dark and remote places to watch dumb beasts

tear each other apart. They found this amusing. If they had known anything about

history, they might have argued that this was a step up from the Romans watching

humans tear one another apart in the arena, but they didn’t know anything about

history. They didn’t know anything about the responsibilities incumbent upon a

creature that has a choice about sending lesser creatures to their deaths as

opposed to creatures not having a choice about being sent to their own deaths.

And they couldn’t have parsed, or possibly even read, the previous sentence.

The

upright people in the neighboring towns might have known about the dogfights.

Sometimes the fights got broken up, but not often in rural areas. Local sheriffs

weren’t exactly FBI qualified, and were usually elected. Even the smart law

officers figured the dog fights and other twisted amusements of the backwoods

types was one way to keep them out of town. The churchgoing, chamber-of-commerce

types didn’t want them in their bars, after all.

So the

Callaways and their ilk could operate pretty much undisturbed. They could even

kill one another. Dad Callaway had had three sons. One had gotten into a feud

with some other clan across the hills and got himself killed. Dad Callaway

wouldn’t tell Billy Bob who’d done the deed, because Billy Bob was dumb enough

that he’d march right over there and continue the fight. That would end up with

Dad being the only Callaway left, and Dad Callaway didn’t want to get killed

himself. He was smart enough to know which clan was bigger and tougher. The

other-side-of-the-hill clan had dumped Leroy’s body off at the front of the

Callaway's dirt driveway, and Dad Callaway had buried his son right there.

That

was the way Dad Callaway lived, both as a coward and as a bully. And now, he was

upset about a dog for which he had paid good money - $40 - not living up to his

perceived potential. The Callaways would pick up strays, go to city pounds, get

culled dogs from too-large litters, steal pets and put them in the fenced yard

with Killer. Killer would always dominate, but he wouldn’t kill. He wouldn’t

even harm another dog that had stretched the neck in submission. Confronted with

the fact that the dogs they brought in wouldn’t force Killer into viciousness,

the Callaways attempted to do the job themselves.

They

started by putting Killer in a cage not much larger than the dog. Killer

couldn’t move around. He had barely enough room to stretch out or turn over. The

first night they put him in the cage, he whined piteously and gnawed at the

gate. “Now, we’re gittin' somewheres,” said Dad Callaway, sitting in an old

chair that smelled of stale beer and mold. “First, they’re sad. Then, they’re

mad,” he intoned. Billy Bob and Lenny nodded as if some great wisdom had just

been imparted.

For

the first few weeks, when either Billy Bob or Lenny would come out of the house,

Killer would try to rise up in his cage to greet the humans. He’d try to wag his

tail, but it kept hitting the rear end of the cage. In response to the dog’s

greeting, the brothers would beat on the cage with a stick, or poke the dog

until Killer yelped in pain. Or, they’d fire a gun. Killer hated that. It scared

him terribly. The loud Bang! of the gun filled the air around him and slammed

into those sensitive ears that stood up like the ears of a fruit bat. Killer’s

ears were muscular like every other part of his body. He actually could fold

them as if trying to keep that terrible noise from penetrating, but it didn’t

work. Lenny or Billy Bob would laugh to see those ears crumpled over.

Truth

be known, though, Lenny’s laughing was just show. He didn’t like torturing the

dog. In the Callaway clan, he couldn’t not participate. But he didn’t enjoy it.

If he’d come upon the cage alone, well away from his brother and father, he’d

talk to Killer with kind words. “You’re a tough little guy, ain’t cha,” he’d

say, and Killer would look at him with those big, brown eyes as if trying to

decipher the words, as if trying to pick some comfort out of what had become a

miserable life.

Lenny

would stick his fingers through the grate and scratch Killer’s head. Then he’d

stop, and let his fingers dangle there, Killer would look at him, then nudge his

fingers with his nose. Lenny would scratch his head again. One night, Lenny had

an idea. “You want to learn a trick, Killer?” as if dogs didn’t want to learn

tricks. Lenny would scratch Killer’s head through the grate, then let his

fingers dangle in the vicinity of the gravity lock on the cage. Once in a while,

pushing up with his nose in hopes of getting more attention, Killer would

accidentally push the gravity lock up, and the door to the cage would swing

open.

“Now,

if ya’ll ever git in real trouble, you jist push up this heah latch, and run

like hell. Run!” Lenny would say, and grab both of Killer’s stubby front legs

and pump them. But then Lenny would go to bed, and Killer’s lonely reality would

set in again.

The

Callaways wouldn’t feed him anything except dog parts - skin, entrails, bones.

Dad Callaway seemed to think that kind of diet would give Killer a taste for dog

meat. Dad Callaway’s knowledge on the subject of diet was not too far removed

from Nero’s views on the subject of community fire protection. This wasn’t a

good diet for Killer, and it didn’t do what Dad Callaway intended. Feeding a

canine dog meat will no more make him a killer than feeding a cow grass will

make the cow a specialist on lawn care.

On top

of that, Killer didn’t get much exercise. Occasionally, they let Killer out to

run in the yard, and it was a tribute to the loyalty gene in dogs that Killer

didn’t just use the opportunity to run full speed to the horizon. None of the

fat Callaways could have pursued him much beyond the end of the driveway. The

only walks Killer got were when he was leashed to the back of the pickup and had

to trot along behind while whoever was driving drank beer and listened to the

radio. Every once in a while, they’d forget about the dog and go too fast,

dragging Killer along the gravel road by his neck.

This

was the dog’s life. He never got to play. He never got to run through the green

pastures. He never got to track down the source of the myriad of smells that

hang in the air around any dog. He never got to experience the thrill of the

smell of danger lurking in the scents left around a tree, nor to experience the

bravado of marking his territory over the mark of another, much more feral

canine that had learned to live in the woods without the help of man. He rarely

knew the pleasure of being scratched behind the ears, or snatching a flung treat

out of the air. He never knew love.

The

only thing keeping Killer alive was his natural resiliency and the fact that Dad

Callaway had paid a whole $40 for him. Even those two factors weren’t going to

keep him alive much longer. The stupid diet he was on was robbing him of his

vitality and sapping his immune system. What finally saved him from the

Callaways was Billy Bob’s cruelty and fear of disease.

One

day, Billy Bob was goading Killer in his cage with a stick. Someone had told

Billy Bob that dogs’ noses were very sensitive, and Billy Bob took this to mean

that it was easier to hurt a dog by hitting the dog on the nose than, say, his

rump. So Billy Bob was trying to poke Killer on the nose when he accidentally

poked the dog in the eye. Killer yelped and cowered toward the back of the cage,

blood running from his right eye. Bill Bob didn’t care that he had hurt the dog,

but he did care that he may have damaged a family investment. He even more

worried about having damaged the dog to an extent that it might cost money to

fix it.

That

would make Dad Callaway extremely mad. Billy Bob didn’t know the truth of how

his other brother had died. All he knew was what Dad Callaway had told him, and

what Dad Callaway had told was that Dad himself had killed the other boy for

misbehaving and buried him right there at the end of the driveway. Billy Bob

wasn’t quite sure what degree of offense would merit the death penalty, but

damaging a dog on which Dad Callaway had pinned such hopes might qualify. A dog

couldn’t fight with one eye, could he? Billy Bob wondered to himself.

He

opened the cage door and pulled Killer out to examine the wound. He dabbed some

disinfectant on it. While he was doing that, he noticed Killer didn’t have any

fur on his lower jaw and chest. Billy Bob, that paragon of bravery in bars,

dropped Killer like a hot coal. He hopped up and away from the dog, shaking his

hands like he’d been snake bit. “Sheet, Lenny,” he yelled. “That there dog’s got

the mange, or some sich, an’ I teched him! Damn me for a fool, get some bleach

and water outn heah, quick like, and don’t tech that there dog!”

Dad

Callaway, classified as one of America’s unemployed and therefore home, came out

to see what all the commotion was about. “Dad, he’s got the mange! Lookit his

front! He tain’t got no hyar. Let me shoot him, Dad. We cain’t keep no dog

‘round heah with the mange, can we?” Billy Bob blathered.

Dad

Callaway looked at his son and cuffed him out of the way, which Dad Callaway

could do because he weighed in at around 350 pounds and had that lie about the

third brother buried at the end of the driveway to back up his discipline. Billy

Bob glared at his father, but didn’t retaliate. Killer cowered in a corner of

the yard by a fence, watching his tormenters and trying to lick at his wounded

eye. The whites of his eyes appeared as he looked fearfully around, perhaps

wondering if there was any more suffering that could possibly be added onto the

burden he already was bearing.

Killer

hadn’t done anything wrong in the context of canine behavior. He’d just bonded

with the wrong humans, but they were the only humans he’d ever known. Killer had

known only three humans, having been sold as a puppy. He couldn’t help bonding

with them; he was a dog. Dogs don’t need to be forced into loyalty with beatings

and the threat of a brother killed and buried at the end of the driveway. Killer

was a member of a species that had entered into a partnership with mankind that

had endured through seventeen millennia. As man had marched upward to claim

dominance over all the earth, the dogs had marched right along beside, eyes

bright, tongues hanging and brains alert for the next instructions.

And

what was this tiny but not unrepresentative splinter of mankind doing with its

dogs? Putting them in pits and watching them fight because that was the best

entertainment they could muster up on a Saturday night. No longer did Man need a

watchdog; he had Brinks. No longer did Man need a tracker; he had the FBI and

paper trails. No longer did Man need a companion to patrol the perimeters of the

cornfields; he had electric fences and traps and poison. No longer did Man need

his friend to lie outside the tent and watch while he slept; all the bears were

locked up in Yellowstone, and all the mountain lions had been killed to make way

for the cow. Dogs now worked where they could, still doing what they were asked

to do, even to the extent of strutting like fatted sows and walking in useless

figure eights in incredibly meaningless dog shows. Or jumping down into the pits

and killing or dying for the amusement of their masters.

Killer

hadn’t made the grade. Like the man who had sat up on the roof all night waiting

for the sunrise, it had finally dawned on Dad Callaway. Killer would have been

dead at that moment, except Dad Callaway had paid $40 for that mutt, and he was

going to get that money back.

“Pick

‘im up and put ‘im in the truck,” he told Lenny. “We’re goin’ to St. Louie. A

friend o’ mine up there sol’ me that dawg, and we’re goin’ a give him back. But

don’t hurt him no more. We might be able to do this pleasant like, but maybe

not, so git my guns too.” The three of them got into the truck and drove off

into the late afternoon, north on Interstate 55 toward St. Louis.

They

arrived in the wee hours of the morning when it was still dark, which was okay

with Dad Callaway, because he knew Tommy would have been at the local tavern

until closing time. Then, unless he’d gotten lucky, he’d have wandered back home

to fall into a boozy sleep. Knowing Tommy, Dad was fairly certain he hadn’t

gotten lucky. The three Callaways burst into Tommy’s apartment and strode into

his bedroom. “Git up, Tommy. We gotta talk,” yelled Dad Callaway.

Tommy

opened red, swollen eyes in confusion, trying to figure out where he was and who

was there with him. He fumbled for the light before he realized it was on. He

recognized the Callaways standing there and looked at the clock. “Goddamn it,

Dad, it’s 4 a.m. You ain’t got the manners God gave a skonk. What the hell do

you want?” he asked.

Dad

pulled up his chair next to the bed and sat his bulk down. His two sons stood

menacingly behind him, Billy Bob absently slapping a short, hardwood rod into

his left palm. It made the same sound that it would make if slapped into a face.

Dad leaned over and glared at Tommy, who was trying to sit up in bed. “I want

that $140 back I give you for that wuthless hound you sold me. You remember

Killer, that pit bull that couldn’t miss? Well, he missed. That dog’s a no-count

coward, won’t fight, an’ I want my money back. You kin have that shit-for-brains

dog back too. You feed ‘im.”

Tommy

squirmed around in the bed, looking unhappy. “Fust of all, you din’t give no

$140 for that dawg. You gave 40. An’ you bought a pup. No one knows how a pup is

gonna turn out. Everone knows thet. A deal’s a deal, Dad, an’ that’s all they is

to it,” Tommy finished, squirming some more and trying to back off from the

looming bulk of Dad Callaway.

The

mouth on top of that bulk opened to say something, but all that squirming by

Tommy had had a purpose. He’d finally found the Smith .40 cal. automatic that

had been under his pillow, and put two rounds - tap, tap - into the chest of Dad

Callaway sitting not more than three feet away. Then Tommy rose and put five

more shots into the real threat in the room, Billy Bob. All five hollow points

had plowed into Billy Bob’s abdomen before the fact that he was being killed

registered on the bully. Still, the big man staggered toward Tommy, tripping

over Dad Callaway who moaned in his dying agony on the floor. Tommy put two more

bullets into Billy Bob’s chest. All that gave Lenny time to run out of the room,

out of the apartment and into the night, abandoning the truck, the Callaway home

and the Callaway heritage.

Hearing the gunshots, Killer had similar views about the Callaway family. The

noises scared him terribly, but he was locked in his cage. “If ya’ll ever git in

real trouble, you jist push up this heah latch, and run like hell. Run!” Killer

remembered. He was alone in the dark in a strange place with strange smells and

the sharp, brief blasts of gunshots reverberating through the night. If this

wasn’t “real trouble,” he couldn’t imagine worse. Killer nuzzled the latch,

popped it up, and the cage door swung open. He jumped out into the bed of the

truck, then off the tailgate and ran down the street, away from the hated truck

and away from the family that had not only rejected his love, but almost

destroyed his capacity for love.

Killer

knew what he had escaped from, but the solid little dog didn’t know what he had

escaped to. It was December in St. Louis, a cold, wet, dreary time of the year.

It wasn’t the deadly cold of the Mountain West, but the damp, chilly cold of the

Midwest. Killer padded slowly down the street, occasionally looking over his

shoulder to see if the faded red pickup was following. Except for the incessant

itching of his chest and his sore eye, Killer was in fairly good shape. One

thing the Callaways had never done to Killer was to starve him. They might not

have given him Science Diet, but dogs can survive on food that would be

repulsive to humans. “I ain’t a gonna starve no investment to death,” the late

Dad Callaway had observed.

But

after close to a week on the streets, Killer was learning about hunger too. His

short fur didn’t give much protection against the cold, so his hunger grew as

his body burned fuel to keep him warm. As he padded through the back streets and

alleys, wary of any human contact, he learned how to find food in garbage cans.

He did this during the night. Knocking over garbage cans during the day brought

yells, and thrown rocks, and sometimes a truck that looked too much like the

Callaways’ old beater. So Killer would run, which accomplished two things: it

kept him away from the dogcatcher, and it kept him away from anyone who might

have helped him.

And he

itched. He didn’t know what it was, but demodetic mange had established itself

on his chest and had spread all over his front quarters and up under his chin.

The microscopic mites were feeding rapaciously on his body and driving him

half-crazy. He’d scratch furiously, but only succeeded in opening sores. The dog

sighed and stretched out along a tawdry wooden fence next to a scraggly yard in

one of the numerous fading suburbs nestled up to an ailing St. Louis, towns not

big enough to support themselves, but jealous of their autonomy, as if a

Jennings could ever attain the historic stature of a St. Louis. Among the normal

city services such towns didn’t do well was animal control, so Killer managed to

run free through December and into January when the damp chills could turn into

truly killing temperatures.

The

cold was particularly hard on him now. He hadn’t had much of a coat to begin

with, being a shorthair, and now the mange was stealing large chunks of that.

The dog’s skin began to crack beneath the triple assault of biting midges,

furious scratching and cold. He slept only fitfully, trying to curl his body

around the bare spots on his chest.

A

couple of people tried to help him. One woman came close enough, only to recoil

in disgust when she saw the raw sores on his hairless chest. And this was no

poster dog for the humane society. He had those unmistakable heavy jaws and wide

head of a pit bull, and therefore also had the attendant bad reputation. He had

what appeared to be a boil on his right eye, the legacy of the late Billy Bob’s

stick. And he limped. The dog had an old wound from a particularly vicious kick

that had become arthritic in the cold.

Killer didn’t trust anyone

anymore. He especially distrusted males, having known only males in his whole

life and having suffered terribly at their hands. They’d hurt his body and his

psyche. Every morning during his puppyhood, he’d awakened and eagerly greeted

his humans, his humans, he had thought. Unabashedly wagging his tail

until the movement involved his whole butt, he’d greet one of the three

Callaways every morning, and every morning, his greeting was answered with a

slap, or a kick, or a sharp word until all the love that once welled up in him

was swallowed, and like the sweet meat of a nut, encapsulated in a hard shell.

His current misery exacerbated his unhappiness. He began to sit near the big,

busy roads, watching the trucks go by with their glass eyes and their black

feet, wondering if maybe he ought to cross that road and let whatever would

happen, happen.

970-723-8639

|